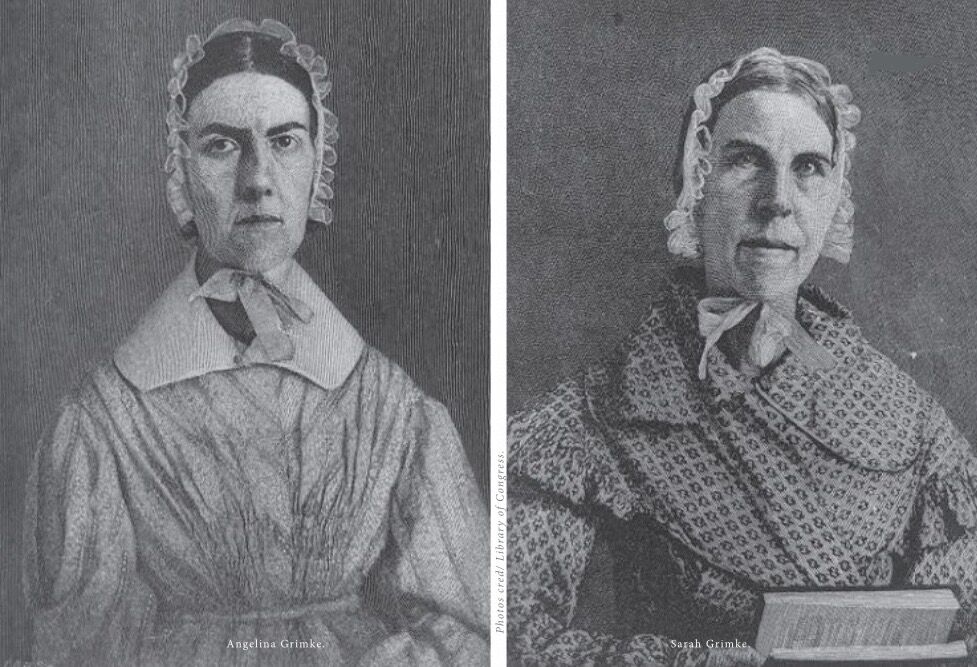

Where would American politics be without women? This doesn’t just apply to those intrepid souls of all parties who run for public office but references the voice of every woman who is an integral part of the political process. Women comprise the largest voting bloc in the country. That wasn’t always the case, of course, since women have only had the right to vote for less than half of our country’s history. That right didn’t come without a fight — and two of Charleston’s own were on the front lines of the battle.

If you’ve lived in the Lowcountry a while, you’ve likely heard of the Grimke sisters, the famous abolitionists who grew up in a local slave-owning family in the early 1800s. What you may not know is that they helped to ignite the national women’s movement nearly a century before

The family lived downtown at the Heyward-Washington House on Church Street and later moved to 321 East Bay Street where the sisters spent their formative years. As adults, the two sisters moved to Philadelphia and were introduced to the Society of Friends (Quakers). They embraced the church’s views on the abolition of slavery and saw women in ministry positions. However, a woman speaking in public was otherwise unheard of in the 1830s. Therefore, their activism in the anti-slavery movement initially limited them to small gatherings of women in the homes of other abolitionists. The two helped to establish the New York Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1837 and became known for their brilliant speeches. Eventually, they were compelled to begin a speaking tour, often addressing thousands of both men and women at packed venues.

The idea of two women speaking publicly to large (and gender-mixed) audiences brought them prominence as well as controversy. Even among abolitionists, there was debate as to whether women should take the stage. The anti-slavery movement eventually split into two factions over “the woman question,” with one group excluding women from participating at all.

The sisters distanced themselves from the church when male Quaker ministers preached of “the dangers which at present seem to threaten the female character with widespread and permanent injury” and urged women to remember their “appropriate duties.” But that didn’t stop the Grimke sisters. Angelina addressed a committee of the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1838, turning her anti-slavery speech into an argument for woman’s suffrage. She asserted that if women had the right to vote, they could help end slavery, claiming “What can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence?” She made history as the first woman in America to speak before a legislative body. As a result, other women were inspired to speak out about a woman’s right and responsibility to participate fully in society.

Sarah drew a parallel between the disenfranchisement of women and of enslaved Africans, writing in her “Letters on Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman” that both groups were deprived of a formal education in a male-dominated society that labelled them as mentally inferior. She argued that the subjugation of women benefited men, comparing it to the benefit that plantation owners received from the enslavement of Blacks.

At the first women’s rights convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, prominent suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony led the group’s initiatives for constitutionally guaranteed rights to adopt its Declaration of Sentiments which was influenced by the writings of the Grimke sisters.

When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Angelina “True, we have not felt the slaveholder’s lash; true, we have not had our hands manacled, but our hearts have been crushed … I want to be identified with the Negro; until he gets his rights, we shall never have ours.”

The following year, the two women moved to Boston with Angelina’s husband, the famous abolitionist Theodore Weld, and the couples three children. By then, Sarah had retired from active participation in the women’s movement. But the publication of British philosopher John Stuart Mill’s book, “The Subjection of Women” in 1869 posed many of the same arguments the sisters had pushed for decades — and prompted the 77-year-old Sarah to walk through her Hyde Park neighborhood selling 150 copies.

In the general election of 1870, the sisters led a group of 42 women to the polls to vote at Hyde Park Town Hall. The flummoxed town official did not stop them but rather put their ballots in a separate box which were, of course, not counted. The publicity from this event led other groups of women to take similar stands, fanning the flames of the feminist movement. When the Massachusetts Woman’s Suffrage Association was established, Sarah and Angelina both served as its vice presidents at the ages Of 78 and 66 respectively.

Neither woman lived to see the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 but are remembered as possibly being the first leaders in the women’s movement. They are buried in Boston’s Mount Hope Cemetery where a historical marker was installed at their graves several years ago. A bridge in Hyde Park was named for them in 2019.

The best-selling novel by Sue Monk Kidd titled “The Invention of Wings” as well as a reprint of the landmark non-fiction work, “The Grimke Sisters from South Carolina,” have catapulted the sisters into the national limelight in recent years. And local tour guide Lee Ann Baines offers a tour of downtown Charleston that focuses exclusively on these remarkable and courageous women.

When you soon make your voice heard in the voting booth, think of the Grimke sisters whose fight for the rights of women helped to make your vote count.

By Mary Coy