Eliza Lucas Pinckney grew up on a sugarcane plantation in Antigua. Like other children of wealthy planters on the Caribbean island, she was sent to school in England where she studied literature, writing, music and botany, classics that would prepare her for a suitable marriage.

Caribbean to Charleston

After Eliza returned to Antigua, a slave uprising threatened the planters’ security and in 1738, her father, George Lucas, lieutenant governor of Antigua, relocated the family to the Lowcountry where he had amassed three large plantations. Hampton, to the northeast of Charleston, encompassed a massive 25,000 acres at its height. Beyond was Waccamaw, a 3,000-acre property. Three miles southwest of the city was Wappoo, a 300-acre tract. The two latter plantations have since been destroyed, and according to historian Lee Brockington, even the best archaeologists have been unable to locate the sites where they once existed.

After Eliza returned to Antigua, a slave uprising threatened the planters’ security and in 1738, her father, George Lucas, lieutenant governor of Antigua, relocated the family to the Lowcountry where he had amassed three large plantations. Hampton, to the northeast of Charleston, encompassed a massive 25,000 acres at its height. Beyond was Waccamaw, a 3,000-acre property. Three miles southwest of the city was Wappoo, a 300-acre tract. The two latter plantations have since been destroyed, and according to historian Lee Brockington, even the best archaeologists have been unable to locate the sites where they once existed.

Tragically, Eliza’s mother, Ann, died after the move. Two years later, in 1740, her father was called back to Antigua to serve in active military duty during a war, leaving Eliza alone to run the plantations. As the oldest child with two brothers, Thomas and George, who were attending school in England, Eliza became the overseer of the family properties.

The Indigo Experiment

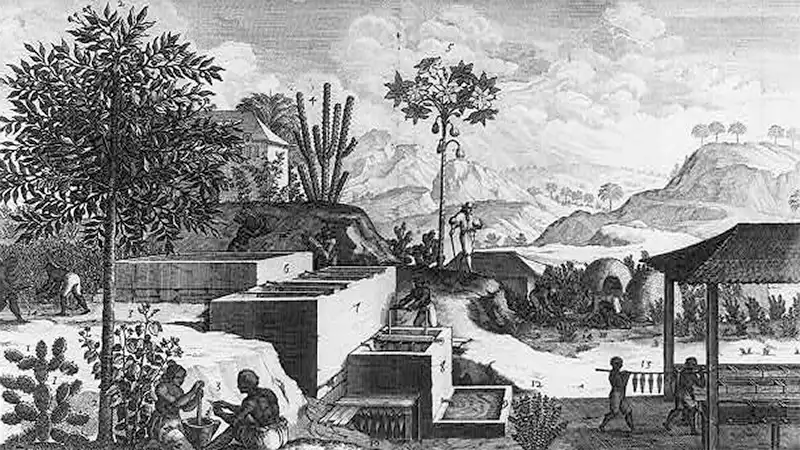

Eliza’s father sent indigo seeds from Antigua for her to experiment with at Hampton Plantation, which had become her main residence, according to historian Elizabeth Huntsinger. She explained that many Lowcountry planters had also attempted to grow the crop, valuable for its purplish-blue dye, but had yet to experience success. During the sweltering summer months when most planters traveled to escape the miserable heat, humidity and mosquitoes, the young and relentless Eliza stayed on the plantation with her slaves, working to crack the code. After persisting for four years, their hard work paid off and Eliza is remembered as the first woman to achieve success with the indigo crop.

Eliza’s father sent indigo seeds from Antigua for her to experiment with at Hampton Plantation, which had become her main residence, according to historian Elizabeth Huntsinger. She explained that many Lowcountry planters had also attempted to grow the crop, valuable for its purplish-blue dye, but had yet to experience success. During the sweltering summer months when most planters traveled to escape the miserable heat, humidity and mosquitoes, the young and relentless Eliza stayed on the plantation with her slaves, working to crack the code. After persisting for four years, their hard work paid off and Eliza is remembered as the first woman to achieve success with the indigo crop.

At 21, Eliza married Charles Pinckney, 45, and they had four children together, according to the National Park Service (NPS). Their first son, Charles Cotesworth, born in 1746, was a statesman and military officer who went on to be a signer of the U.S. Constitution. Their second child, George Lucas, was born in 1747, but passed away soon after. Their only daughter, Harriott, was born in 1749. The youngest son, Thomas, was born in 1750 and went on to serve as a diplomat and statesman.

“Eliza managed to continue working directly with plantation operations while her family grew,” The NPS shared. “While raising their young family, Charles Pinckney contracted malaria and died in 1758. Eliza remained a widow the rest of her life, continuing to manage the plantations her husband left behind.”

Exports to England

Further, “She sent a substantial export of indigo to England as proof of her efforts. In addition to economic motives, indigo production also succeeded in the Lowcountry because it fit within the existing agricultural economy. The crop could be grown on land not suited for rice and tended by enslaved people, so planters and farmers already committed to plantation agriculture did not have to reconfigure their land and labor. In 1747, 138,300 pounds of dye, worth £16,803 sterling, were exported to England. The amount and value of indigo exports increased in subsequent years, peaking in 1775 with a total of 1,122,200 pounds, valued at £242,295 sterling. England received almost all Carolina indigo exports, although by the 1760s a small percentage was being shipped to northern colonies.

“By the beginning of the American Revolution, indigo made up one-third of the exports from South Carolina. In less than 50 years, the market had grown substantially. However, the tension with the British and the establishment of the East India Trading Company led to the diminishing of the Carolina indigo trade. After 1776 as the United States established itself as an independent nation, trade with England essentially ceased. Indigo remained a popular commodity within the region, and was traded with other states’ resources.”

Huntsinger, who formerly worked as a ranger at Hampton Plantation, said she had the opportunity to study research papers kept in the office’s library. The documents were helpful for piecing together the later years of Eliza’s life since her personal journals ended in the mid-1760s.

In the early 1770s, Eliza developed breast cancer and her family sent her to Philadelphia, where she would have access to the most modern medical treatment. In 1773, at age 71, Eliza lost the battle and was buried there in St. Peter’s Churchyard. George Washington requested the honor to be a pallbearer at her funeral.

SC Business Hall of Fame

In 1989, according to the NPS, Eliza was “the first woman inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame for her contributions to agriculture and economic growth. In 2008, she was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame.”

By Sarah Rose