In today’s world, we sometimes take it for granted that women hold jobs in fields that were once male-dominated. For centuries, pursuing their life’s ambitions was a right most women were denied. And until 100 years ago, women were even denied the right to vote or to attend the same colleges as men.

A lot has changed. Most Americans today don’t think twice about women in fields such as engineering, construction, law and medicine. In fact, most of us will be treated by a female doctor at some point in our lives. So, who was the first Charleston woman to blaze that trail?

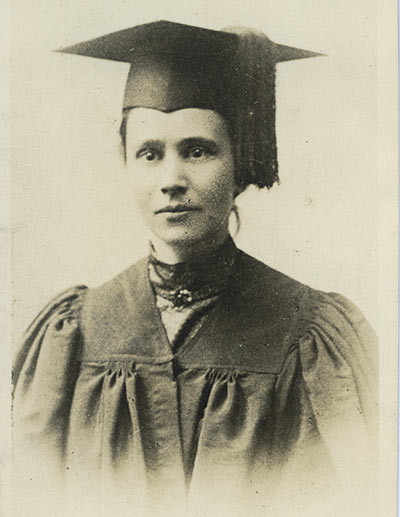

Sarah Campbell Allan was born in 1861, eight months into the Civil War. She grew up as a child of privilege but, as an adult, was denied admission to the College of Charleston because it was an all-male institution at the time. Instead, she attended Charleston Female Seminary, an elite private school located on St. Philip Street, just around the corner from the college. Its founder, Henrietta Aiken Kelly, established the school after her own attempts to gain admission for women to the College of Charleston had failed.

Allan went on to study premedical training at the all-female Columbia College in the state capital. She graduated in 1894 from the Women’s Medical College program at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, an institution founded by America’s first female physician, Elizabeth Blackwell. The following year, Allan held a residency in the psychiatric clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital before coming home to take South Carolina’s first ever medical board exam. She was the only woman to sit for the exam and scored the highest grade of the 14 candidates taking the test, becoming the first female licensed physician in South Carolina.

Allan went on to study premedical training at the all-female Columbia College in the state capital. She graduated in 1894 from the Women’s Medical College program at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, an institution founded by America’s first female physician, Elizabeth Blackwell. The following year, Allan held a residency in the psychiatric clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital before coming home to take South Carolina’s first ever medical board exam. She was the only woman to sit for the exam and scored the highest grade of the 14 candidates taking the test, becoming the first female licensed physician in South Carolina.

In 1895, the governor offered Dr. Allan a full-time position at the state’s Hospital for the Insane, in Columbia. There she treated female patients while also teaching physiology and anatomy to nursing students. After 11 years, she returned to Charleston to care for her ailing father until his death.

In Charleston, Dr. Allan occasionally consulted on psychiatric cases, although she never established a practice in the Holy City. She made her mark on history by following her dream, proving the potential and contribution of women in the medical field. The Medical University of South Carolina holds Dr. Allan’s papers, photographs and scrapbooks at its Waring Historical Library.

Dr. Allan died in 1954 and is buried at Magnolia Cemetery.