ELIZABETH MATTHEWS HEYWARD AND LOIS HALL

During the British occupation of Charleston from May 12, 1780, until Dec. 14, 1782, Charleston’s population was divided in half between loyalists and patriots, many of whom were arrested and sent to St. Augustine for imprisonment. One such nationalist was Thomas Heyward, Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence. His wife Elizabeth Matthews Heyward and her pregnant sister Lois Hall (whose husband had also been arrested) were left behind with their children in the house at 87 Church St. on the embattled peninsula.

Under British rule, an illumination decree was established, requiring Charleston residents to place a lit candle in their windows in celebration of Redcoat victories near and far. When news of a win in North Carolina arrived, Heyward refused to light candles and place them in the windows. Soon came a knock at the door from a soldier, demanding Heyward comply with the ordinance. However, Heyward stood firm. When she was informed of the next British triumph, she did not illuminate again. On this occasion – according to historian and board member of the Charleston Tour Association Lee Ann Bain – a mob of royalists convened on the house, threw trash at its walls, smashed the windows with bats and broke down the door. During the siege, Hall was in the throes of giving birth and whether from pain, fear or a combination of both, tragically, she died. When soldiers came to the house the next day offering to make repairs to the property, Heyward turned them away since they had known there were two women alone in the house, yet they had done nothing to ward off the rioters.

Because of her bravery and conviction throughout the occupation, Heyward was given the title “Queen of Love and Beauty” by George Washington at a ball in Philadelphia, where she moved to reconvene with her husband who had been treed but was banned from Charleston.

SEPTIMA P. CLARK

Photo provided by WalkCharlestonHistory.com.

Nearly a century later, just after the Civil War ended in 1865, the Avery school on Bull Street in downtown Charleston was established as a private institution for educating Black teachers. In 1955, the school closed when students transferred to state-funded Burke High School. The building remained empty until 1980 when the College of Charleston partnered with the community to save the structure, which survived threats from the KKK in the 1960s as well as abandonment. In 1985, the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture opened. Dr. Tamara Butler, Ph.D. and executive director, said of the center’s extensive archives and impressive library, “Our job is to bring history home.”

Indeed, some of our nation’s most important leaders in social justice attended Avery, including Septima Poinsette Clark. After her graduation in 1916, Clark couldn’t afford college tuition. At age 18, she took a state examination that gave her the opportunity to teach, although local law dictated that only white educators could teach Black students on the peninsula, and Black teachers had to work in sea island communities such as Johns Island. In 1919, Clark began working with the NAACP and spent the next four decades establishing “citizenship schools” where she taught literacy to thousands of interracial people so they could read the constitution and understand their rights. “I believe unconditionally in the ability of people to respond when they are told the truth. We need to be taught to study rather than believe, to inquire rather than to affirm,” Clark said.

In 1945, Clark helped win equal pay for Black teachers. Then when South Carolina passed a law in 1965 banning city and state employees from any involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Clark refused to give up advocating with the NAACP for the integration of public schools. Consequently, she was fired, lost her pension and was thrown into prison on several made-up charges such as illegal alcohol possession. The accusations were later dropped. When Clark was released from jail, Martin Luther King Jr. invited her to work with him by expanding her model of citizen schools across the South.

In 1987, at 87 years of age, Clark passed away and was buried at her Old Bethel United Methodist Church. She leaves behind a legacy as the grandmother of the Civil Rights Movement, of which she said, “The air has finally gotten to the place that we can breathe it together.”

THE POLLITZER SISTERS

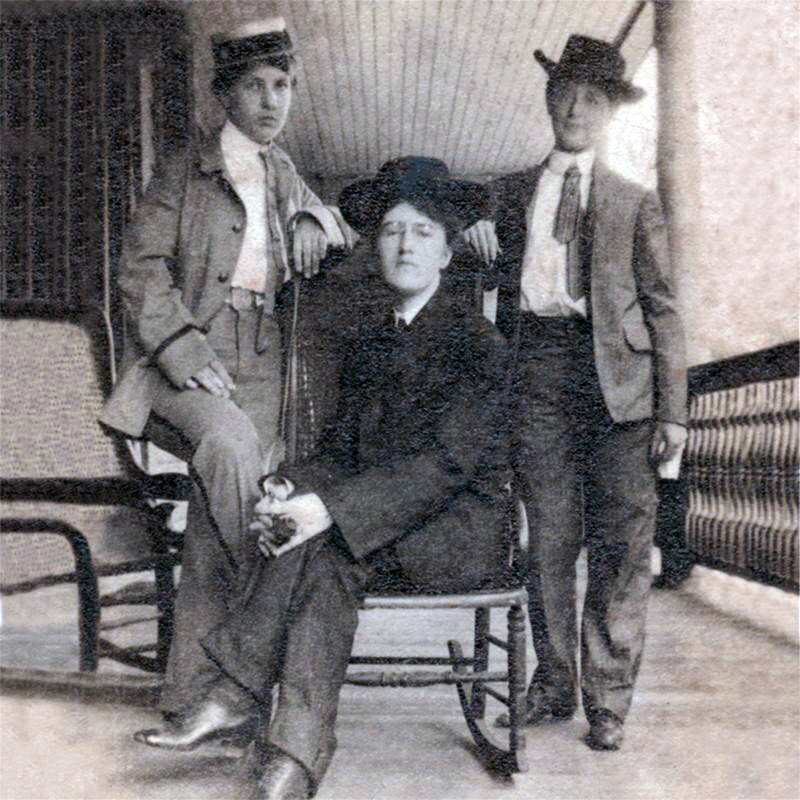

Photo provided by CharlestonWalkingTours.com.

While Clark was starting her journey in the fight for civil rights, the Pollitzer sisters Mable, Carrie and Anita were arguing for women’s suffrage. The eldest sister, Mable, graduated from Columbia University in 1906 and returned to her hometown of Charleston where she became a teacher at Memminger for the next forty years, creating the natural science department and the first sexed program for her female students in their senior year. A charter member of the Charleston Equal Suffrage League, Mable later joined the National Women’s Party (NWP) as South Carolinas state chair. In the 1930s, along with Laura Bragg, director of the Charleston Museum, Mable also established the first free library to serve both Black and white residents.

Meanwhile, since women who were pursuing a higher level of education were forced to leave the state, Mable’s younger sister Carrie petitioned mens organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce to allow women to attend the College of Charleston. According to Bain, by 1918, Carrie won the battle and the first women were admitted.

At 25 years-old, the third Pollitzer daughter, Anita, was the youngest of the NWP officers to serve. As secretary of the legislative committee of the NWP, Anitas claim to fame was her work that helped to pass the 19th amendment, which was codified into the Constitution on Aug.26, 1920, after decades of suffragettes overcoming violence and resistance from authorities and spectators.

These stories don’t begin to scratch the surface of the strong women of Charleston who pioneered the past, laying the foundation for the present. May we preserve their hard work for the future. D

To learn more history about our local femmes fatales, visit WalkCharlestonHistory.com

By Sarah Rose

Photos provided by Charleston Walking Tours