“Whatever women do, they must do twice as well as men to be thought half as good. Luckily, this is not difficult.” – Charlotte Whitton, former mayor of Ottawa

Over the ages women have been called “the weaker sex” and stereotyped as such in novels, television and movies. Though female voices are arguably being heard more now than ever, the fight started long before the efforts of recent generations. Women right here in the Lowcountry have been speaking up for longer than many realize to fight for a place in social and business worlds. In a letter to the editor of a Charleston newspaper in 1743, one female reader demanded that if women could not have more freedom, then men should have less. A male writer countered that she should find herself a husband. However, even centuries ago, there were local women who didn’t allow that mentality to stand. Female researchers, artists and entrepreneurs began making their marks on the area from the time of its founding.

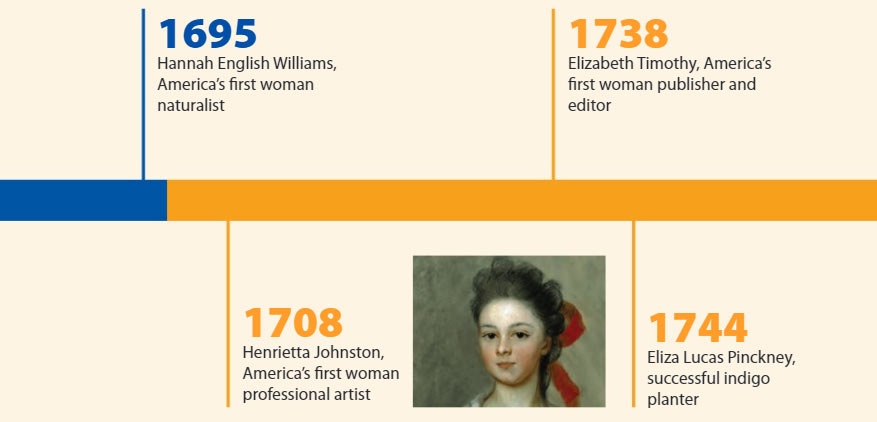

One notable name is Hannah English Williams. Williams came to the Lowcountry as it was just being settled. Considered the first woman naturalist in America, she catalogued flora and fauna on her husband’s Ashley River plantation in the 1690s. She sent samples to the preeminent Royal Society of Scientists in London. Reptiles, insects and even live birds were shipped. A few species of American butterflies are named for her.

Another early Charleston resident, Henrietta Johnston, was America’s first professional woman artist. As an Irish widow and mother of two young children, she earned income by painting portraits. She moved to Charleston in 1708 with her second husband, the rector of St. Philip’s Church. He acknowledged that if not for the money she made painting portraits in the new world, “I should not have been able to live.” Johnston painted a number of prominent local figures and introduced the use of pastels to American artists. About 40 of her portraits remain, including some at the Gibbes Museum of Art.

Two decades after Johnston moved into the area came Elizabeth Timothy. In 1734, this trailblazing Philadelphian arrived in Charleston when her husband founded the newspaper, South Carolina Gazette. She was pregnant with their ninth child when he died in 1738, and she continued publishing the newspaper that he and Benjamin Franklin had started, thereby making her America’s first female newspaper publisher and editor. She bought out Franklin’s stake in the paper and ran the publication for five years, while caring for her large family. Once her son Peter took over, she operated a separate enterprise, printing legal documents, posters, advertisements and stationery. She also owned a bookstore. After Peter’s death, she helped her daughter-in-law continue to publish the newspaper.

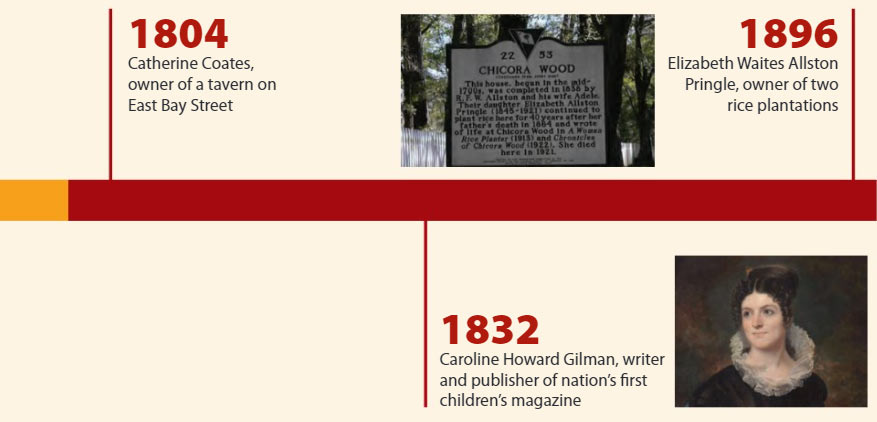

Though women such as Timothy were already shattering glass ceilings, it was difficult for a female to begin or inherit a business in the 18th and 19th centuries. If a man owned a business, his wife did not inherit it unless it was stipulated in his will. Conversely, if a woman business owner married, her business automatically became her husband’s property. But in 1817, Catharine Maria Sasportas, a biracial woman in Charleston, was granted a deed by her husband to run her own business. Mr. Sasportas made his wife the sole proprietor, agreeing that he would not be involved in any of the dealings. It was likely a shop, since married women were restricted from operating any business other than a bakery, grocery, restaurant or retail enterprise.

However, more changes were on the horizon. Elizabeth Waites Allston Pringle was born in 1845 to a wealthy Lowcountry family. When her father died, she and her mother ran a boarding school until his estate settled. She married years later, but her husband and son died shortly thereafter. Pringle purchased her husband’s plantation from her in-laws and inherited her father’s land after her mother’s death. Thus, she became the owner of two plantations. With no agricultural experience, Pringle somehow managed the two rice plantations. When local rice production died out, she reinvented the business by planting peach orchards and renting land to hunters. She wrote a column for the New York Sun about being a woman planter, and her articles were later published in the book, “A Woman Rice Planter,” a bestseller.

By the 20th Century, Susan Dart Butler began making waves for women of color. Butler studied at the Avery Institute, the prestigious local school for Blacks. Her father, a prominent Baptist minister, had founded a vocational school for Black children in Charleston. She became its director after his death in 1915 and converted her father’s personal library there into a lending library. With donations from wealthy benefactors, she expanded it to 3,600 books. The Dart Hall Library eventually became part of the Charleston Free Library, the predecessor of the Charleston County Public Library.

Another graduate of Avery, Huldah Josephine Prioleau, was one of the state’s first Black woman doctors. After finishing medical school at Howard University in 1904, she returned to Charleston and opened a private practice on Spring Street, purchasing two adjacent houses— one as her office and the other as rental property. Prioleau also ran a wellness program from her home, taught medicine at the Cannon Street Hospital and helped establish the Charleston County Medical Association.

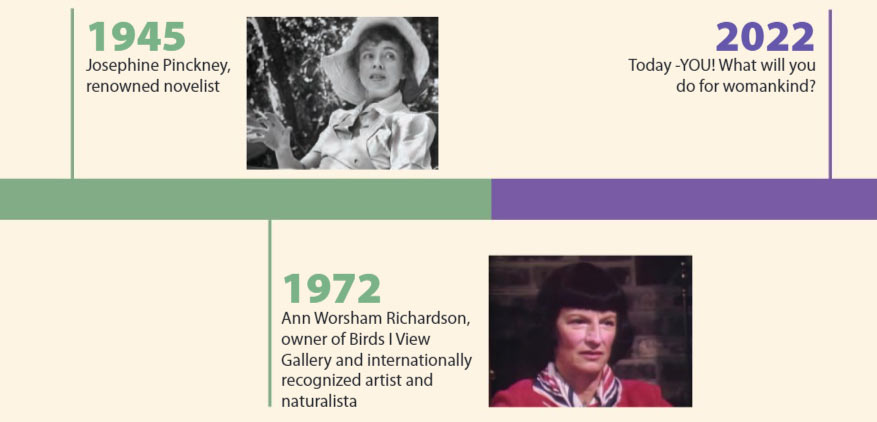

Today’s women entrepreneurs continue to establish businesses in male-dominated fields. Women-owned businesses come in all shapes and sizes.

For example, Erin Williams, owner Charleston Towing and Roadside said, “I grew up around heavy equipment and got my CDL at 19.”

Now Williams manages the office duties while operating tow trucks. She works hard to gather clients, maintain machinery and run the business. Because of the precedents set by those who came before her, she can succeed a little more easily today. It doesn’t matter that her field is male-dominated; it matters that she saw a place to make her mark on the world. It matters that women stood up for her hundreds of years before her birth. It matters for every woman alive today.

By Mary Coy