The Charleston Magazine Tour of Homes issue would be remiss without acknowledging the enslaved people who were in large part responsible for building and running the grand historical houses for which Charleston is famous, as well as raising the families who lived in them.

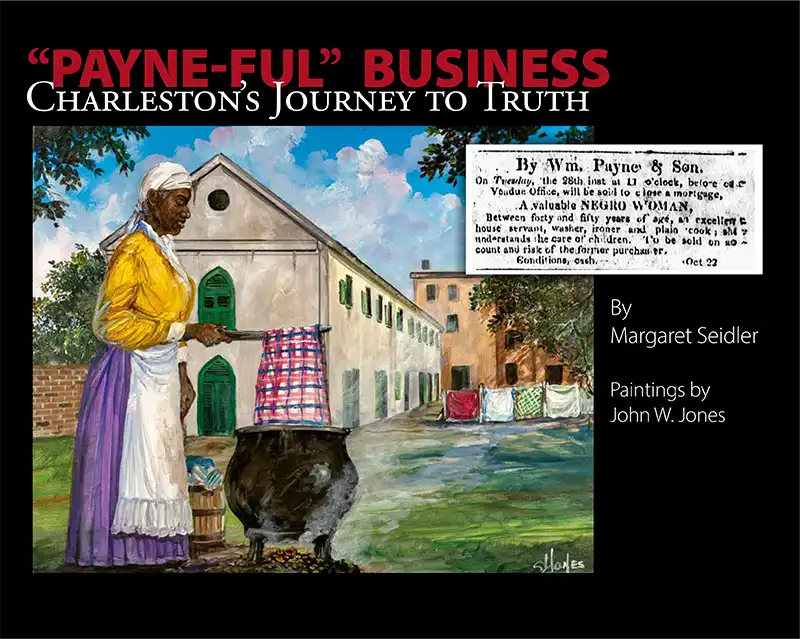

In her soon-to-be-released book “‘Payne-ful’ Business, Charleston’s Journey to Truth,” native Charlestonian Margaret Seidler takes readers on a heart-wrenching journey back in time to honor the enslaved laborers who by 1730 made up two-thirds of South Carolina’s population. These highly skilled workers — brick moulders, bricklayers, carpenters, cabinet makers, painters, tanners, silversmiths, rice planters, cotton harvesters, carriage drivers, tailors, seamstresses, washers, ironers, butchers, cooks, waiters, night nurses, child-minders and more— shaped the community in which we live today.

Seidler’s journey into this history started accidentally when, in 2018, an unbeknownst cousin of color named Pearlstine Simmons Scott reached out on an ancestry platform to introduce herself and make a connection. Intrigued, Seidler dug into her family’s background and stumbled upon a buried secret: her fourth great-grandfather, William Payne, was the largest transactional slave-trader in Charleston in the early 1800s. Searching through digitized copies of newspapers on NewsBank and Readex at the SC Room in the Charleston County Main Library, and sourcing physical newspapers at the Charleston Library Society, Seidler discovered that between 1796 and1834, Payne placed over 1,100 advertisements for the sale of individuals, families and plantations in the City Gazette & Commercial Daily Advertiser and the Charleston Courier, resulting in the brokerage and sale of a staggering 9,268 human beings. Rather than hiding the horror a history like this is sure to spark, Seidler decided to illuminate her family’s background by writing a book and speaking publicly about it. All proceeds from the book will be donated to local causes supporting historical research and racial justice.

During Seidler’s research, African art dealer and gallery owner Chuma Nwokike reached out to Seidler to connect her with John W. Jones, renowned artist of “Confederate Currency: The Color of Money.” A descendent of enslaved ancestors, Jones created a series of over sixty paintings that pay homage to the enslaved people described in Payne’s advertisements. Jones displayed the portraits in a recent exhibit at City Gallery, an ideal location as slave trading took place all over Charleston, including on the waterfront and also in the very homes in which the brokers lived. Since 1865, however, the facades of many of those houses and buildings have changed dramatically, due to multiple fires that raged across the peninsula, Union soldiers burning the city beyond recognition and a devastating earthquake that shook Charleston to its core during post-war redevelopment. Thus, behind the walls of the historical homes that still stand today lie stories not just of the gentry class who entertained in them, but also of those who endured back-breaking labor to maintain the grandiose structures that we continue to appreciate today.

By Sarah Rose